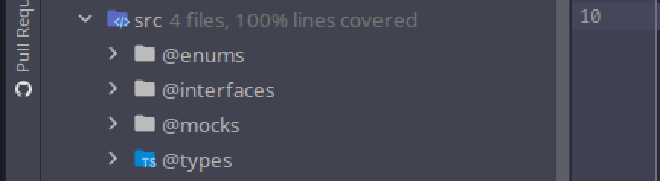

TL:DR I generally have some variation of this set of folders that I add to all of my TypeScript projects:

src/

├── @enums/ <- project-wide Enumerations

│ ├── AsyncStates.ts <- (described below)

│ └── HttpStatusCodes.ts <- (described below)

├── @interfaces/ <- project-wide Interfaces

├── @mocks/ <- mocks used in local dev and tests

└── @types/ <- project-wide Types

└── AsyncStatus.ts <- (described below)

As a longtime JavaScript developer I admit that it took me a long while to warm up to TypeScript. However, after fully

embracing TypeScript the one thing that still irritated me was a seemingly growing amount of non-JavaScript related

files bloating up my project folders - ie. the superset part of TypeScript: types, interfaces, and enumerations. When I

am looking at a folder with more than six (6) *.ts files it is nice to know that I am looking at app logic and/or unit

tests.

I believe the first time I noticed an at folder it was something along the lines of @models in one of the company’s

architects seed projects. I thought the @ prefix was a novel idea being legal in JavaScript/TypeScript and it really

called out to me that this was a special folder. At the time our stable team was working on a really interface-heavy React

front-end and some of the service and component folders were growing quite large with bespoke interfaces and types mixed

in with the business logic and (too few) unit tests.

One weekend I decided to create a spike branch and move as many of the interfaces and types as I could into @types

and @interfaces folders. Not only did it declutter some service and component folders I also managed to find a couple

of places we had duplicates and more than one error. This pattern proved to be very popular with the team and we expanded

the idea to include an @enumerations folder to house some enumerations we had created to lend meaning to some of the

magic numbers and string values peppered around the project. After a few years using this pattern I have not had a team

yet that disliked, or really had any problem with it.

Some more detail and examples of my reasoning follows.

@enums (or @enumerations)#

Here we give meaning to groups of numbers or strings, say your backend had a numeric field AddressType - what does that

1 in the field really mean? By creating an AddressTypes enumeration we no longer have to remember 3 means “Business”

or that 5 stands for “Cabin by the Lake”. For a real-world example this particular enumeration helps me keep a lot of

magic numbers out of my React front-ends and NodeJS backends:

@enums/HttpStatusCodes.ts

/* eslint-disable no-magic-numbers */

enum HttpStatusCodes {

Ok = 200,

Created,

Accepted,

NoContent = 204,

MovedPermanently = 301,

Redirect = 302,

BadRequest = 400,

Unauthorized,

Forbidden = 403,

NotFound,

InternalServerError = 500,

NotImplemented,

BadGateway,

}

export default HttpStatusCodes;@interfaces#

The majority of the interface definitions I put here describe the DTO’s coming

from my services. Since I come from a C# background I like to preface all of my interface names with “I”, as in

IUsersResponse, IWidget, etc. - I find that it helps me differentiate interfaces at a glance from types or classes.

example:

export default interface IUser {

id: number;

name: string;

username: string;

address: {

street: string;

suite: string;

city: string;

zipcode: string;

geo: {

lat: number;

lng: number;

};

};

phone: string;

website: string;

company: {

name: string;

catchPhrase: string;

bs: string;

};

}@types#

Really just what it says, types that apply project wide. I feel the best example is a combination of an enumeration and type that I find handy when creating Redux Toolkit slices that utilize thunks:

@types/AsyncStatus.ts

import AsyncStates from '../@enums/AsyncStates';

type AsyncStatus =

| AsyncStates.Idle

| AsyncStates.Pending

| AsyncStates.Success

| AsyncStates.Fail;

export default AsyncStatus;@enums/AsyncStates.ts

enum AsyncStates {

Idle = 'IDLE',

Pending = 'PENDING',

Success = 'SUCCESS',

Fail = 'FAIL',

}

export default AsyncStates;Work together like so to better describe the intent of the values being used:

store/slices/user.ts

import { fetchUsers } from '../../services/user/UsersApi';

// NOTE: not all interfaces end up in the global folder if they make

// more sense at a granular level

export interface IUserSlice {

current: IUser | null;

users: Array<IUser>;

status: AsyncStatus;

error: string | null;

}

export const initialState: IUserSlice = {

current: null,

users: [],

status: AsyncStates.Idle,

error: null,

};

export const user = createSlice({

name: 'user',

initialState,

reducers: {

clearCurrentUser: (state: IUserSlice) => {

state.current = null;

},

setCurrentUser: (state: IUserSlice, action: { type: string; payload: number }) => {

const user = state.users.find(x => x.id === action.payload);

if (user) {

state.current = user;

state.error = null;

} else {

state.current = null;

state.error = 'user not found';

}

},

},

extraReducers: builder => {

builder.addCase(loadUsers.pending, (state: IUserSlice) => {

state.status = AsyncStates.Pending;

});

builder.addCase(

loadUsers.fulfilled,

(state: IUserSlice, { payload }: PayloadAction<Array<IUser> | undefined>) => {

state.status = AsyncStates.Success;

state.users = payload ? (payload as Array<IUser>) : [];

// or you could make it an additive operation

// state.users = [...state.users, ...(action.payload as Array<IUser>)];

},

);

builder.addCase(loadUsers.rejected, (state: IUserSlice, action: any) => {

state.status = AsyncStates.Fail;

state.error = action.payload as string;

state.users = [];

});

},

});Bonus: @mocks#

Since some of the response signatures from the services can be quite complex we found it convenient to collect all of our mocks in a single location to be easily reused across multiple unit tests. It is also handy for the rest of the team to not have to reinvent the wheel each time they are writing new code relating to the previously mocked values.

Another bonus that came out of creating these mocks is we found that it allowed us to develop service and component code in

parallel with the backend. The front-end developer collaborates with the backend dev to get the proposed shape of the DTO

that will come out of the API. From there it is simply a matter of defining the interface for said data and developing a

mock return value in the @mocks directory. To simulate the interaction for your application you can pipe mocked values

through the service code until the backend is ready for you to pull the live version. And triple-bonus you now have valid

mocks for all unit tests around the service consumption.

example:

import IBlock from '../@interfaces/IBlock';

const mockChain: Array<IBlock> = [

{

timestamp: 1,

lastHash: '-----',

hash: '=====',

data: [],

difficulty: 3,

nonce: 0,

},

{

timestamp: 1664912323208,

lastHash: '=====',

hash: '12d331b40d8ef653827c9e43502c3ee73232038be01937f1cd8328fe699a85a8',

data: ['lookit', 'da', 'birdie'],

difficulty: 2,

nonce: 8,

},

{

timestamp: 1664912364866,

lastHash: '12d331b40d8ef653827c9e43502c3ee73232038be01937f1cd8328fe699a85a8',

hash: '458059ca76b703b0be6d7f30b80fb44ad3b8436348032f59efcf5056930b2b38',

data: ['data', "come'n", "get'ur", 'data'],

difficulty: 1,

nonce: 1,

},

{

timestamp: 1664912386011,

lastHash: '458059ca76b703b0be6d7f30b80fb44ad3b8436348032f59efcf5056930b2b38',

hash: '15c3351282a1c3a5744e101c005243a3df0b9ce781c3a76d55f850c28fd3dbdd',

data: ['why', 'not', 'both?'],

difficulty: 1,

nonce: 2,

},

{

timestamp: 1664912416611,

lastHash: '15c3351282a1c3a5744e101c005243a3df0b9ce781c3a76d55f850c28fd3dbdd',

hash: '2f0211da93f4ef426f4588c1ba36db5cdbc6802e8ef8156494f9507af253da74',

data: ['not', 'your', 'friend', 'buddy'],

difficulty: 1,

nonce: 4,

},

{

timestamp: 1664912432611,

lastHash: '2f0211da93f4ef426f4588c1ba36db5cdbc6802e8ef8156494f9507af253da74',

hash: '12e5596c6f124fc0989a2f61cc79b48b5e16a8ce5abfb43ad47d8a531c406d1f',

data: ['not', 'your', 'buddy', 'amigo'],

difficulty: 1,

nonce: 1,

},

];

export default mockChain;in use:

import mockChain from '../../../@mocks/blockchain';

import * as chainApi from '../../services/ChainApi';

jest.mock('../../services/ChainApi');

describe('components / App', () => {

it('should match the snapshot', async () => {

(chainApi.fetchBlocks as jest.Mock).mockResolvedValueOnce(mockChain);

const component = render(<App />);

expect(component.container.firstChild).toMatchSnapshot();

});

});Which may also be easily reused in the negative test:

// just making something up here as the BlockChain class

// itself actually prevents tampered chains

const badChain = [...mockChain];

badChain[1].lastHash = '1am4b4dh4xx0r';

(chainApi.fetchBlocks as jest.Mock).mockResolvedValueOnce(badChain);I hope that maybe this can help some of you reduce the cognitive load of your larger TypeScript projects. If you have a variation of this that works even better feel free to drop me a line, I would be grateful to hear about it. Huge thanks go to former co-worker and amazing front-end architect Brian Olson for forcing me to use TypeScript until I learned to enjoy it.